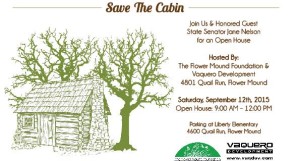

Part 2 of a Series on the Long Prairie Homestead Cabin

Since announcing the marvelous find of the Long Prairie Homestead Cabin inside of a Flower Mound farm house, several descendants of William Gibson and other early settlers have come forward to share information. Many thanks to Larry Briscoe, Lindsey Troublefield, Jeff & Lori Hallford, and Rose Mead for providing ancestry information and sharing in the excitement of this log cabin discovery.

Homestead Cabin inside of a Flower Mound farm house, several descendants of William Gibson and other early settlers have come forward to share information. Many thanks to Larry Briscoe, Lindsey Troublefield, Jeff & Lori Hallford, and Rose Mead for providing ancestry information and sharing in the excitement of this log cabin discovery.

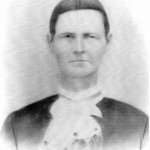

William Gibson patented this property in 1854 and appears to have been the builder and original

occupant of this cabin when it was constructed in about 1860. William Gibson’s parents were William Gibson Sr. and Margaret Armstrong. His parents moved from North Carolina to Tennessee in 1796-97, after the birth of their first son, Jesse. Brother James Gibson was born to them in 1797 and William Gibson in 1801, both in Tennessee.

William married Rebecca A. Wallis in 1826. William, his two brothers, and several family members migrated to Township No. 53 in Platte County Missouri in the 1830s. William and Rebecca Gibson’s children were: Margaret Jane Gibson, 1828 – 1914; John Meritt Gibson, 1830 – 1875; George S. Gibson, 1832 – 1881; Nancy Ann Gibson, 1835 – 1933; Mary Ann Gibson, 1837 – 1885; Martha C. “Mattie” Gibson, 1840 – 1934; Ludecia L.E. “Ludicy” Gibson, 1843 – 1860; and Thomas Benton Gibson, 1848 – 1892. One source shows a tenth child, William Gibson III born in 1850.

The call for settlers to Texas reached Missouri shortly after the Texas Revolution. Sam Houston and the Republic of Texas had cleared the way for the settlement of North Texas with the signing of treaties with nine tribes of warring Indians at Bird’s Fort in 1843, six miles South of Flower Mound.

In May of 1844, sixteen families from Platte County Missouri loaded their wagons to brave their move to the wilds of North Texas. Most were related by blood or marriage. William Gibson, was among this group of early pioneers, as were James Gibson, Jesse Gibson, John Hallford, James Hallford, Owen Medlin, Hall Medlin, and others. They brought their families, their dogs, their guns, and their Baptist religion with them.

The journey was not easy. Swollen rivers and hostile Indians plagued the journey. The 1844 settlers had to camp for three weeks waiting to cross the Trinity River.

The Missouri Colony stayed in the Hallford Prairie area for several months before expanding into unsettled areas of South Denton and North Tarrant County. Many settled in Flower Mound on Long Prairie, where William Gibson built what we now call the Long Prairie Homestead Cabin.

In 1845, James Gibson and John Hallford returned to Platte County Missouri to convince other relatives to return with them to this new land of opportunity in Texas. Between May and September of 1845, several related families sold their holdings in Missouri in preparation for the trip to Texas.

Twelve ox carts of Missouri Colonists were ferried over the Red River on November 1 of 1845, with this second wave of migration. In addition to the families mentioned above, families of Fosters, Allens, Eads, Larkins, Bakers, and Andersons came in the second migration.

Pearl O’Donnell Foster in her book Trek to Texas, 1770-1870 describes life on the trail for these pioneers:

They traveled through the wilderness with few trails, fording the creeks and rivers at their most narrow or low points by oxen and covered wagons, “prairie schooners”. The oxen traveled more slowly than the horses or mules, but were much more rugged and able to take day after day and even months of almost daily travel. The wagons had heavy homespun canvas covers fastened over arched strips of wood …which protected their supplies…At night, they would stop near some spring or flowing stream where fresh water could be found. Here they would start a fire with logs and small underbrush, and prepare their food over the camp fire. Their bread was made principally of crushed corn. The corn was crushed with pistle in a mortar when grist mills were not available. Flour, which had to be milled from wheat could not be milled at the grist mill, so biscuits and white bread were a luxury to be enjoyed only on special occasions on the frontier. Their meat consisted of venison other wild game, which was abundant.

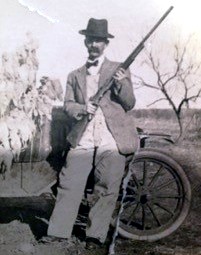

They carried plenty of seed which was carefully guarded as it was needed to seed their fields in the new unsettled lands… On and on they went, traveling by night in the areas known to be inhabited with hostile Indians or bandits…ten miles was a good days journey. The women and children walked much of the time, and the men, when not driving the wagons, rode horseback ahead to determine the best route. These brave, rugged men and women were ever ready to protect themselves against any foe – hostile men or animal. The old trusty flint lock, for which they melted and molded their own bullets, was always at hand and their unerring aim as they would lift their shoulder to this old-time fowling piece, seldom failed to drive away an enemy or bring down game as meat for themselves and loved ones.

Foster describes the trip of the 1845 Missouri Colony migration from Bonham to the Three Forks of the Trinity River:

There were a few settlements along the way but widely scattered along the trail. They passed Col. Geary’s Ranger Station not far from the East Fork of the Trinity. They found no settlers along the Trinity. In the Cross Timbers were droves of wild turkey, buffalo, deer, antelope and wild horses. Panthers and wolves lurked in hidden places, and they were constantly alert for small bands of marauding Indians. Game of all kinds, honey and wild grapes were plentiful. This was indeed a wild but lush and enchanting land. These men were skilled in lumbering, acquainted with hardship and the use of the musket — a strong healthy people who knew how to endure the privation of the early settlers. They were well adapted to the life of a pioneer as this had been the life chosen by their people for more than one generation. Unlike some of the driftwood who migrated west for various reasons and seldom owned land or anything of value, we have found records of purchase and sale of land by several generations in several states.

John A. Freeman came with the second migration of the Missouri Colonists and was brought because he was a licensed Baptist preacher. In those days, a preacher had to carry a bible in one hand and a carbine in the other; he had to be prepared to fight the devil or fight Indians at any moment.

Freeman wrote his version of the trip in 1845. He crossed the Red

River into Texas just north of Bonham on the 1st of November of 1845. They took a direct route to the Three Forks of the Trinity River and passed a company of Rangers stationed on the East Fork of the Trinity. The Rangers were dressed in buckskins and some wore coon-skin caps. Many spent their time drinking bad whiskey and playing cards, in between chasing marauding Indians.

Freeman further states, “From Rowlett’s Creek to the Elm Fork of the Trinity there were no settlers; nothing to be seen but bands of wild horses and droves of deer and antelope. We crossed the last named stream about the 15th of November, 1845, six miles west of Elm Fork, and (settled at) the house of James Gibson” (brother of William Gibson). Timber Creek in Flower Mound is six +/- miles from the Elm Fork and early ownership maps confirm James Gibson patented property at this location in Flower Mound.

Ed F. Bates writes of the Missouri Colonists in History and Reminiscences of Denton County, first printed in 1918.

“They were a peculiar people in some respects. They had but little property among them, and yet they were well enough to do. All seemed to be on an equality, and the sole object in living was to do all they could for the comfort and satisfaction of one another, and to make their way to a better world than this. They were a good people, and could have ruled this county for many years had there been business men among them”.

Our earliest settlers left us a proud history and heritage. They suffered severe hardships, fought savage Indians, and built homes, churches and schools in a wilderness we now call Flower Mound. They were caring people that would risk much to help a neighbor. We should remember them for their strength, sacrifice and compassion. We should honor the lives they led.

This is the second in a series of articles about our early settlers in Flower Mound and the Long Prairie Homestead Cabin. Mark Glover is a native of Flower Mound & Lewisville. Mark is a student of local history, a sustainability advocate, and is well known for his hobby farm – Rheudasil Farms. He is married to Penny Rheudasil Glover, daughter of Flower Mound’s First Mayor, Bob Rheudasil. For over 25 years Mark has helped local businesses to buy, sell, lease, develop, and invest in commercial real estate through his company iMark Realty Advisors. To support Save the Cabin, go to www.TheFlowerMound.com.